HISTORY OF “RESTAURANTS” (NOT WHAT YOU THINK)

Two recipes—one, ancient—follow the story below.

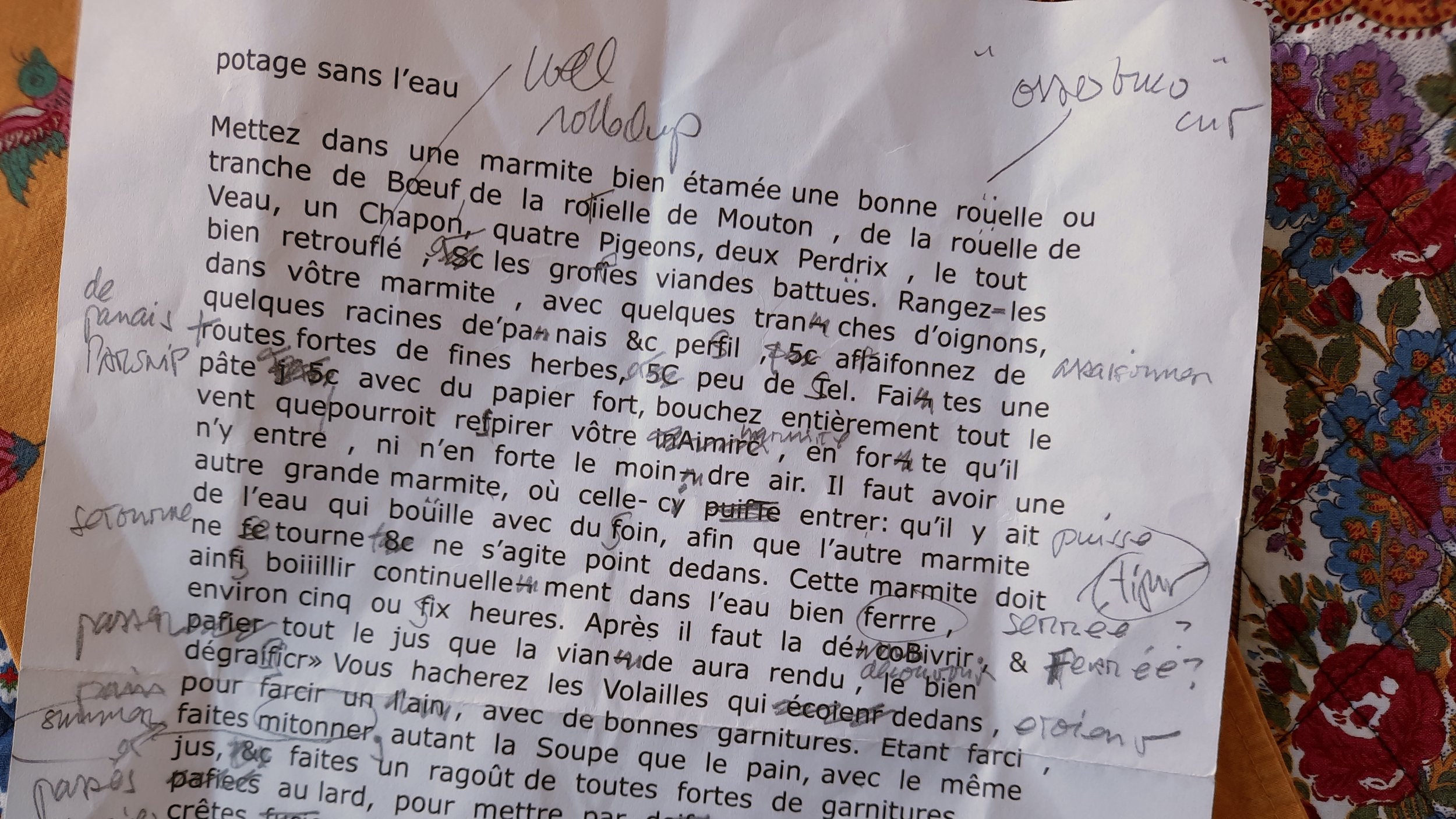

Francois Massialot’s recipe for Potage Sans L’Eau, in the French of his time.

The first “restaurants,” so named, weren’t restaurants, as we understand them.

They were broths, bouillons and consommés, fashioned by cooks in Paris, France, in the mid-late years of the 1700s. Their aim was to “restaurer,” the French for “to restore.” They were restoratives, pick-me-ups, easy-to-digest but fortifying. Cooks who called themselves “restaurateurs” served individual portions of the hot liquids to patrons seated at small, unadorned tables.

The March 9, 1767, edition of the Parisian “L’Avantcourer” (“The Forerunner”), a journal dedicated to “innovation in the arts, the sciences and any other field that makes life more agreeable,” highlighted the “excellent consommés or restaurants” of a Monsieur Minet, which were “carefully warmed in a hot water bath.”

A few months later, in the July 6th edition, L’Avantcourer wrote up Jean-Francois Vacossin, “restaurateur,” who sold his broths “for the re-establishment of good health to those who have weak and delicate chests,” in a public space outside their homes “where they can go both to enjoy the benefits of society and to take their restaurants.”

These first “salles de restaurateurs,” precursors to the sit-down restaurants as we know them and that flowered in France just before and after the Revolution of 1789, were destinations more for the enervated than the hungry in search of a lavish meal.

The first French eating or dining-out places did not serve multi-course meals from a printed or spoken menu because they could not. The enforcement of the guild system in France forbade any but registered “traiteurs” to sell stews, braises or ragouts, that is, dishes that were made up of solid foodstuffs plus liquids.

All the early restaurateurs could sell were the liquids that resulted from heating meats, fowl and vegetables—not the solids themselves. Hence, broths, bouillons and consommés, the first “restaurants.”

A warming restorative broth seems appropriate this time of year. I offer the recipe for the most well-known of its day, Francois Massialot’s (1660-1733) “Potage Sans L’Eau,” “a soup made without water,” first published in 1691 in his revolutionary cookbook “Le nouveau cuisinier royal et bourgeois.” It is an intense set of just juices rendered from very slow cooking of several meats and vegetables.

Massialot’s original recipe stipulated using capon, pigeon and partridge, as well as veal, all meats difficult to find (or, not to say, undesired) by the contemporary cook. So, I substitute similar proteins such as chicken and duck. Too, Massialot requires two large “well-tinned” pots, one that will fit inside the other for a slow simmer of “5-6 hours.” By and large, we don’t sport that sort of kitchen equipment.

Well, he did not own a Crock-Pot or other slow cooker, as we generally do, so my telling of his recipe does. But heed Massialot’s important advice to seal the cooker’s lid extremely well, to prevent any (at all) steam from escaping. (I used two overlapping sheets of heavy-duty aluminum foil.)

I also omit Massialot’s service of the soup in hollowed-out “boules” of hearty bread, along with some cooked veal sweetbreads and uncured pork. (The recipe in the 1705 edition of the same cookbook also recommends cockscombs, ha.) But give your own cooking that rein if you’re up to it.

Massialot’s recipe does not furnish much quantity of “potage”—maybe 2 cups total if you’re lucky—but, wow, is it concentrated and delicious, replete with gelatin and an array of flavors. A “restaurant” indeed. (Also, a significant amount of fat to skim, but also a lot of cooked meats to use in other meals down the line.)

I also offer a recipe for another liquid “restorative” made with leftover pasta and, if you so choose, some of Massialot’s “potage,” diluted.

A cup of Francois Massialot’s Potage Sans L’Eau, an original “restaurant.”

RECIPE: Potage San’s L’Eau

By Francois Massialot, “Le Nouveau cuisinier royal et bourgeois,” 1729 edition, adapted for a modern city kitchen. Translated by Bill St. John.

Ingredients

1 1-pound piece beef shank

1 1-pound lamb shank

1 3-pound frying chicken

2 pounds duck (neck, leg, thigh or combination)

3 medium leeks, white part only, free of soil

1 medium parsnip, partially peeled and split lengthwise

Bouquet garni of “fines herbes” (several sprigs of parsley and tarragon wrapped and tied in the green “leaf” of a leek)

1 teaspoon kosher or sea salt

Directions

Prepare a slow cooker (“crock pot” or the like, with a tight-fitting lid). In the pot, snuggly place the pieces of meat and fowl. Atop them evenly lay the leek, parsnip and bouquet garni. Sprinkle with the salt and cover.

Begin on High heat and when the meat has rendered some juices, turn down the slow cooker to Low. Cover the pot and seal the lid with 2 sheets of heavy-duty aluminum foil, closing all the edges well.

Let the slow cooker cook on Low for 8-10 hours. Remove the solids from the rendered juices and broth, reserving the meat and its bones. Degrease the broth. Take as much meat off their bones as you wish, keeping back any fat or gristle, reserving the meat. Serve the broth, heated well.

Deliciously stretch leftover pasta and rotisserie chicken scraps with a broth flavored with guajillo chiles.

Leftover Pasta Soup with Guajillo Peppers

Serves 3-4.

Ingredients

1 quart broth or stock

4-5 whole dried guajillo peppers

2 cups leftover, cooked small-form or cut-up long-form pasta

Meat from leftover roast or store-bought rotisserie chicken

Directions

Bring the broth or stock to a boil. In 2 cups of it, soak the peppers for 45 minutes. Stem and seed the peppers and slice them into strips. Strain the soaking liquid back into the main stock.

Add the remaining ingredients to the pot and heat through, topping servings with chopped cilantro or flat-leaf parsley.